Volume 1

How Media Narratives Are Fueling Our Vaccine Failure and What Policy Makers Can Do

By Donnie Charleston, Director of Policy & Advocacy

The media plays a major role in public policy formation. Media outlets drive public narratives and serve as a conduit for policy makers to deliver messaging. However, at times the media has a flawed understanding of the public’s interest, which in turn drives the policy narrative. This dynamic can serve to create public misinformation that can have detrimental consequences. With bad information serving as the dominant narrative, the public ends up on the losing end of the equation with bad policy that does not serve their needs. We are in just such a moment now with respect to media vaccine coverage.

Historically, the media has struggled to cover the nuances of vaccine hesitancy responsibly and this time is not different.[1] The result – the proliferation of a potentially dangerous narrative that focuses an inordinate amount of attention on the vaccine hesitancy of communities of color and too little attention to the hesitancy of other demographic groups that pose a greater risk to our collective ability to conquer the virus.

Beginning in late 2020, evidence emerged of vaccine hesitancy on the part of communities of color.[2] This story has consistently received coverage across major media outlets, been reinforced by policy makers, and has even been reinforced by the health care community. And recent reports indicate that the hesitancy narrative is driving public policy. A county official in Jefferson County Alabama reports that state officials have decided not to distribute vaccines in majority-Black neighborhoods because they expect those communities will be vaccine hesitant.[3]

To be sure, vaccine hesitancy is real and represents a threat to communities of color that have been hardest hit by the pandemic, and the issue rightfully deserves our attention. However, the media (and even public health officials) have repeatedly reinforced this narrative of hesitancy by citing data that mistakenly compares vaccinate rates to total population, as opposed to eligible populations. Communities of color have been vaccinated at rates equal to or above their share of age-eligible populations, even though those rates are often well below population levels. That underrepresentation compared to share of the population is a major problem, but the main cause is bad eligibility policy and historic impacts of social determinants of health—not hesitancy!

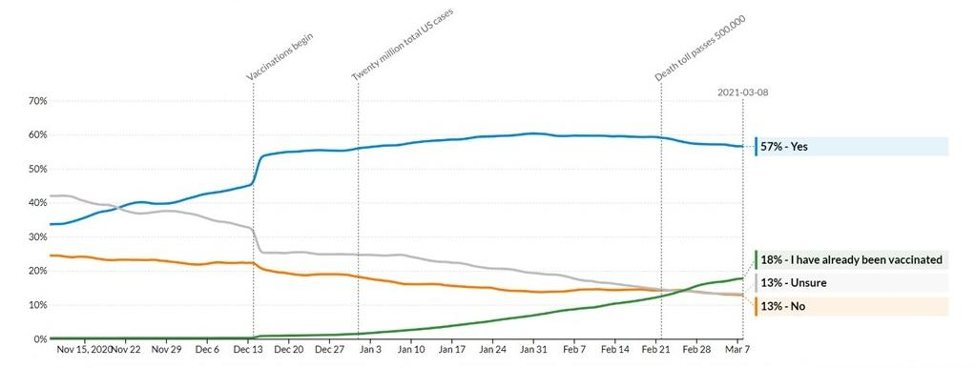

Furthermore, data has recently emerged showing a demographic shift in vaccine acceptance, especially since the election. Yet the media has been slow to respond to this shift and continues to report on the hesitancy angle with a disproportionate attention on people of color. Since November, we have seen a marked increase in vaccine acceptance by African Americans.

[1] Gil, Steven. 2020. Journal of Science & Popular Culture. Volume 3 (2) pp. 125–131.

[2] Funk C, Tyson A. Intent to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine Rises to 60% as Confidence in Research and Development Process Increases. Pew Research Center. December 2020

[3] Shapiro, A. Alabama Official on Vaccine Rollout: ‘How Can This Disparity Exist In This Country?’ All Things Considered. NPR. March 9, 2021

AFRICAN AMERICAN VACCINE INTENT SURVEY RESPONSES

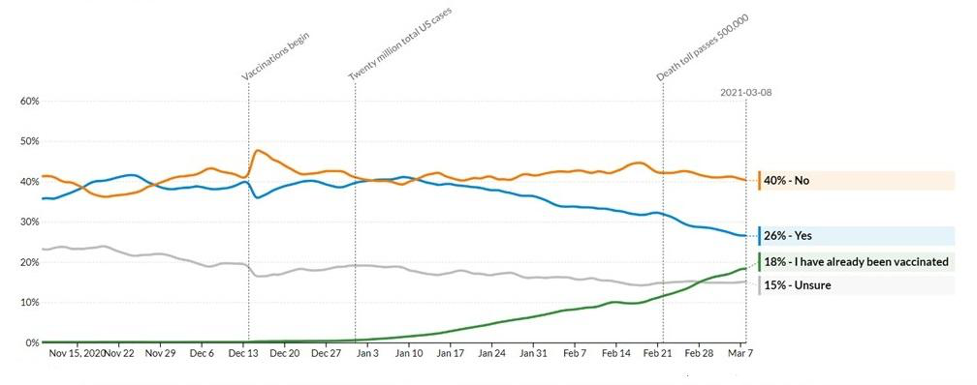

While people of color are showing improved vaccine acceptance, in contrast, there has been a consistent and greater level of vaccine hesitancy among another demographic, notably white conservatives. There has been a consistent 40% of respondents reporting that they don’t plan on taking the vaccine. While Black Americans make up only 12% of the population, white conservatives make up nearly a third of the population. Basic math dictates that as a nation we have a higher hurdle to overcome in addressing the hesitancy in that community as it poses a greater threat to our collective health.

Source: Civiqs

REPUBLICAN VACCINE INTENT SURVEY RESPONSES

Moreover, the continued media missteps can feed a narrative of “virus threat” posed by people of color. For example, recent news coverage by some news outlets has increasingly focused on a narrative that ties the immigration issue to the “threat of unvaccinated migrants” with headlines like: Surge in COVID Positive Migrants Released in the US, and Closed Mexico migrant camp’s 800 residents reach US — regardless of COVID status. Combined with a continued focus on African American hesitance threatens to create a narrative that blames people of color for our nation’s inability to recover from the pandemic. This is all the more pressing given the potential for a “vaccine stall” as the broader population is eligible to take the vaccine.

Analysis by Public Democracy has found that with respect to Latino audiences, there has been a vacuum in vaccine coverage, and that vacuum has been filled by disinformation. Their research has uncovered that the Spanish-speaking audiences are more likely to see search results that reference Sputnik, the Russian vaccine. This is part of a wider disinformation campaign unmoved by the US State Department. This represents a failure of our public health system and our media infrastructure to serve the needs of this population. Public Democracy has launched a wider vaccine campaign focused on leveraging peer-to-peer online communications to shift organic referral systems to counter these negative trends. We highlight below the need for greater investments to broaden and scale this type of work.

The result of these collective failures is that at present we are ill-equipped to mount a sustained frontal assault on the pandemic. The prognosis for a fall recovery is in jeopardy if we collectively fail to get this right. Despite the recent increase in vaccine production, if we fail to effectively adopt an equity lens throughout every facet of the work, we risk squandering the recent opportunity provided by increased vaccine availability. Overemphasis on narratives like “minority hesitancy” also creates an environment where failures of policy or access are able to be excused or only recognized too late because “experts” expect those communities not to participate. This risks a vicious cycle of self-fulling prophesies as communities that are expected not to participate run into barriers that build frustration and lack of faith in the systems.

Vaccine equity refers not only to fairness in the distribution and allocation of resources, but also a responsibility to report on the needs of a community in a way that informs that very allocation. We recognize that many news outlets are operating with good intentions and concern for the health of people of color. But, media campaigns and stories with flawed data and messaging can do more harm than good.

In future installments we will look at other facets of equitable vaccine distribution, but for now we highlight three research-informed actions policy makers and the media can take to ensure a sustainable pandemic recovery for all of America.

Source: Civiqs

Policy Recommendations

LAUNCH MEDIA FOCUSED RESEARCH INITIATIVES & PARTNERSHIPS

The United Kingdom has launched an initiative focused on establishing greater synergy between media outlets and the research community as it relates to combatting vaccine misinformation, and ensuring that high value vaccine information reaches audiences. We need a similar scale initiative in the United States. Our approach in the US has been scatter shot and the media landscape demonstrates a lack of concerted effort and coordination. Google and others have already demonstrated a willingness to step into the fray, but they can’t go it alone. Leaving such a vital issue to be solved by the marketplace is a recipe for disaster. Solving this will require a level of government-media-research community synergy on a scale in which we’ve never attempted. But, it is critical that we do so before it’s too late. This will require federal leadership along with strong leadership from the major actors in the private sector.

INVEST IN STRATEGIC MESSAGING THAT SPEAKS TO MULTIPLE AUDIENCES

It is imperative the media, along with leaders at every level of governance, recognize and utilize targeted vaccine messaging that is sensitive to political and geographic variation. Researchers from Texas A&M, Oklahoma State, Carleton College, Utah Valley collaborated to examine the effectiveness of vaccine health communication frames on different audiences. They tested frames that focused on personal health risks, economic costs, and the collective public health consequences of not vaccinating. Whereas they found different success rates with each frame, with the vaccine-hesitant audience they found that messages originating from peer sources were most effective. Particularly, those messages “emphasizing the collective health risks of failing to vaccinate, and that feature pre-bunking information about the rigors of expedited clinical trials–was significantly associated with increased vaccination intention.” Their work should be instructive for the media and policy makers as they seek to correct past errors and reach those audiences that are most resistant to vaccination. Given that COVID will be an ongoing health threat requiring annual vaccinations beyond 2021, it is time to invest time, money, and energy into uncovering more insights like these that can inform our ability to improve overall population health.

IMPROVE SYNERGY BETWEEN PUBLIC HEALTH AND MAINSTREAM MEDIA

In October, a call to action was made by an international group of experts from public health, cybersecurity, public opinion research, and communications that focused on the implications of misinformation and vaccine confidence for U.S. national security. They outlined a number of recommendations and chief among them: the rapid launch of an independent panel on vaccines and misinformation; and more concerted and coordinated activity by mainstream and digital media to stop the spread of misinformation and to accelerate collaboration with health providers to amplify scientific content. With such high levels of vaccine hesitancy in America, we recommend going a step further and implementing this structure at the sub-national level. In addition to the national level panel, there should exist state level coordination of efforts that address the specific issues arising in local media contexts. Furthermore, many of the early efforts to address misinformation and mistrust have tended toward “correcting mistaken” beliefs and getting communities that are identified as a “problem” to change their beliefs and take actions. A better approach—both to confronting misinformation and developing agency—is to focus efforts on improved understanding of communities and providing resources to meet needs expressed by these communities and that support them in making more informed choices.