Policy Summary

Under this umbrella, we find a range of approaches that would make targeted reforms and resource investments into the nation’s workforce development system to align it with the challenges of the modern economy and the needs of the workforce. The policy focus would target dislocated workers transitioning to new industries, long‐term unemployed individuals updating their skills to catch up with emerging technologies, and low‐income and entry‐level workers seeking to start their careers. Policies in this arena also provide dedicated funding to support expanded on-the-job training activities by strengthening current policies and increasing the number and ability of employers to use on-the-job training.

Case for Equity

The economy is undergoing significant disruption. The accelerating pace of technology and the continued rate of globalization have wreaked havoc on labor markets and contributed to a growing skills gap (Lerman 2015). Our economy is bifurcating into two segments with tremendous growth in the upper and lower-income groups, and a hollowing out of the middle class (Pew 2015). These trends have had a disproportionately negative impact on rural communities and workers of color. The evidence is clearly visible in the wage gap between white workers and workers of color, the gender gap, and the growing wealth gap which is compounded by these labor market trends (Pew 2016). The effects on rural America are compounding as waves of successive downturns have erased the mobility prospects for generations of workers of all racial groups.

Workforce investment on a massive scale could potentially be a catalyst to increase the labor force participation and productivity of millions of workers and eliminate those gaps. Simultaneously, productivity would unleash a level of economic growth and prosperity that would translate into wealth creation and opportunities for all of America. Citigroup estimates that the racial wage gap costs $2.7 trillion in lost GDP annually, and over the past 20 years, the white gender gap alone has cost the US economy $5 trillion (Peterson, 2020).

Return on Investment

Return on Investment for this policy is rated as MEDIUM. The range of outcomes (returns) from investment strategies with varying outcomes contributes to the scoring of this policy.

Research Base

The research base is rated as being HIGH for this policy area.

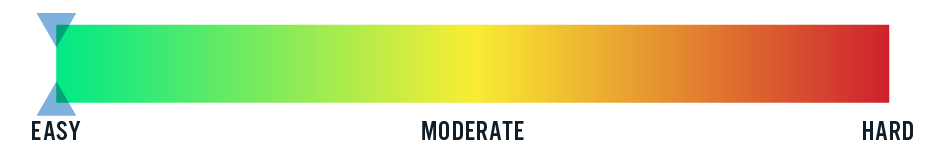

State & Local Ease of Implementation

This policy is rated as having EASY feasibility. The devolved nature of workforce systems provides a degree of autonomy and the ability to implement reforms at multiple levels. The current political climate favors an agenda focused on the interests of working-class and struggling workers. However, the entrenched interests and siloed nature of the system could present a challenge to implementing significant policy reform in this arena.